On December 15, 2025, the Liberal Democratic Party and the Japan Innovation Party— partners in the ruling coalition—launched talks on easing Japan’s tight restrictions on defense equipment exports. The discussions build on the policy commitments the two parties wrote into their coalition agreement in October. They agreed to recommend in February 2026 that the government scrap the current rule limiting exports to five non-combat categories—rescue, transport, alerts, surveillance, and minesweeping. In line with this, the government, led by Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, is aiming to abolish the rule in the first half of 2026.

Itsunori Onodera, a former defense minister who chairs the LDP’s Research Commission on Security, has long maintained that “when countries that share Japan’s values strengthen their defense capabilities, Japan’s own security is reinforced. Transferring equipment contributes to regional stability.” Seiji Maehara, who leads the JIP’s Research Commission on Security, likewise stresses the need to “resolve the contradiction of buying large quantities of lethal weapons (from the United States and others) while refusing to sell any ourselves.”

“Equipment Alliances” on the Rise

For years, Japan effectively maintained a blanket ban on defense equipment exports. In 2014, the administration of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reversed course and introduced the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology. The framework permits exports under three conditions: (1) transfers to parties engaged in conflict are prohibited; (2) transfers must contribute to international cooperation or Japan’s own security; and (3) prior Japanese approval is required for any use beyond the stated purpose or for re-transfer to a third country. Finished products with lethal capabilities were excluded, and exports were limited to the five non-combat categories noted above.In 2020, the first deal under the new framework was approved: the export of air-surveillance radar systems made by Mitsubishi Electric Corp. to the Philippines, a transfer that was carried out in 2023. The Philippines is locked in a dispute with China over the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea and is also geographically close to Taiwan, which China seeks to bring under its control. Japan’s Ministry of Defense hopes eventually to share intelligence derived from the exported radar systems. A four-way information-sharing framework involving Japan, the Philippines, the United States, and Australia is also under consideration.

As the global security environment continues to deteriorate — driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s increasingly coercive military actions — Japan is widening its defense equipment exports to strengthen cooperation with partner nations. In December 2023, the government revised the operational guidelines for the Three Principles, allowing the “reverse export” of finished licensed products back to their original licensors. The United States, which has been supplying weapons to Ukraine, was facing shortages in its own stockpiles. In Japan, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Ltd. manufactures MIM-104 Patriot missiles under license from U.S. defense contractors Lockheed Martin and RTX, and these missiles have subsequently been exported to the United States. On November 20, 2025, Chief Cabinet Secretary Minoru Kihara confirmed that “the transfer to the U.S. side has already been completed.”

In March 2024, the government again revised the operational guidelines, allowing the export of lethal equipment to third countries—limited to finished products developed through international joint programs. The change was made with Japan’s next-generation fighter in mind, a project it is co-developing with Britain and Italy and aiming to introduce in 2035. Eligible destinations are restricted to 16 countries that have concluded defense equipment and technology transfer agreements with Japan, including the United States, Germany, Australia, Singapore, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand. Countries where active fighting is underway are excluded.

In August 2025, Australia announced plans to acquire up to 11 modified Mogami-class frigates from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries for its next-generation fleet, with operations targeted to start in 2030. The two countries will also work together on developing the modifications. Australia shares Japan’s concerns over China’s growing maritime presence in the western Pacific.

Scrapping the ‘Five Categories’ Limit

Japan’s defense equipment exports may look as if they are gaining traction, but headline cases—like the missile shipment to the United States or exports tied to joint development programs—are, in effect, exceptions. Since Japan introduced the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology in 2014, only one export has actually gone through under that framework: the radar systems delivered to the Philippines. The underlying rule that limits exports to just five non-combat categories remains the biggest obstacle to any real expansion.If the five-category rule is lifted, Japan can expect its security cooperation with allied and like-minded partners to accelerate. In Japan–Philippines defense ministerial discussions, the possible transfer of destroyers slated for decommissioning from the Maritime Self-Defense Force has surfaced repeatedly. The leading candidate is the Abukuma-class destroyer escort — a highly versatile vessel equipped with anti-submarine missiles, anti-ship missiles, and torpedoes. For the Philippines, whose naval capabilities remain well behind China’s, the addition of these ships would offer a meaningful deterrent against a country that fields nuclear submarines and aircraft carriers. At a Senate committee hearing on October 7, 2025, Philippine Navy Vice Admiral Jose Maria Ambrosio Ezpeleta said the country hoped to obtain “three ships, if possible.”

Japan is also working to provide the Philippines with systems for information processing and command-and-control. Manila has also expressed interest in the Ground Self-Defense Force’s air-defense missiles. If these transfers go ahead, the Philippines would be able to carry out the entire air-defense chain using Japanese-made equipment—from detecting missiles and other threats with Japanese radar to processing the data, coordinating the response, and intercepting the threat. This would also open the door to deeper information-sharing between the two countries.

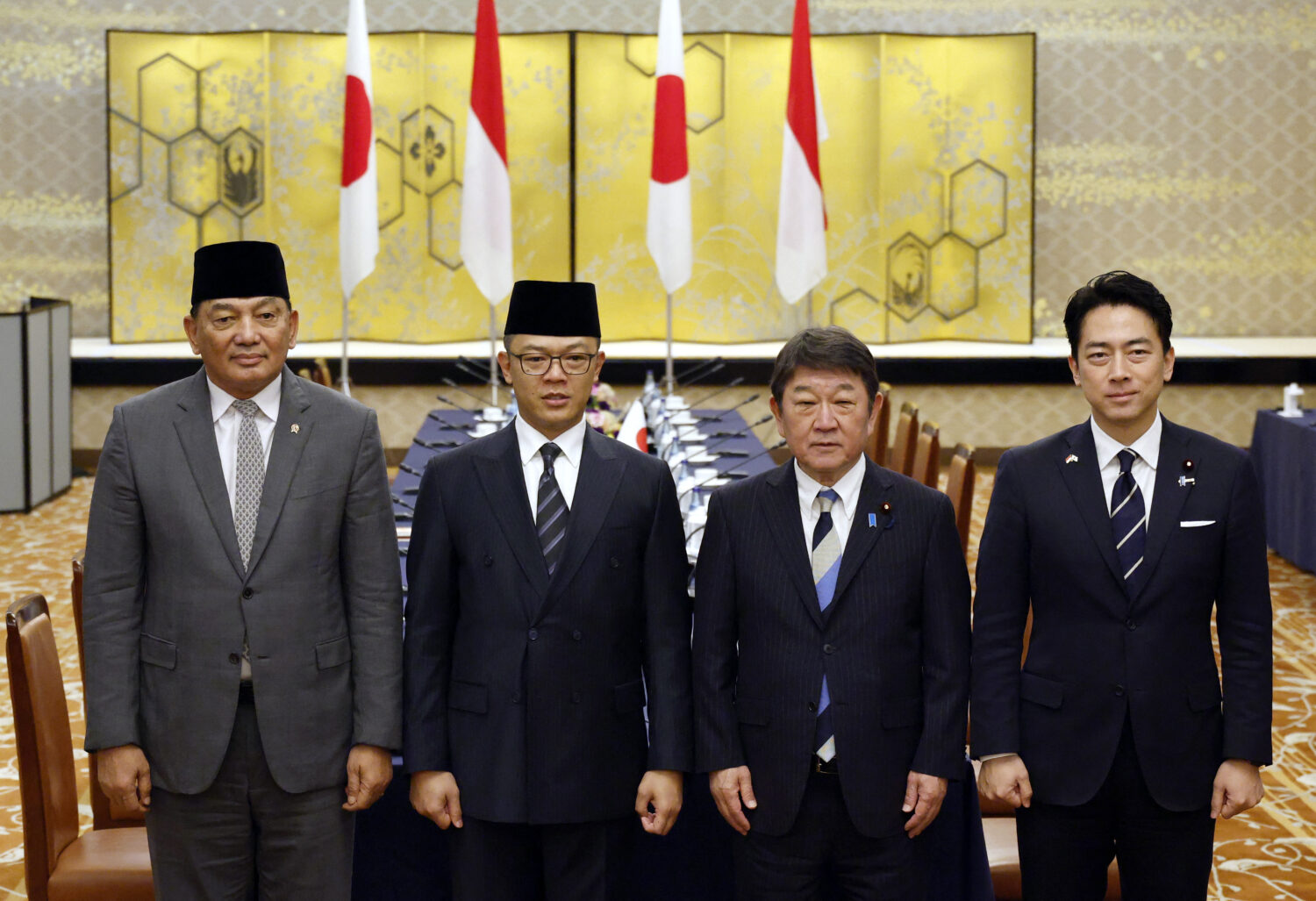

On November 17, 2025, Japan and Indonesia held their “2+2” foreign and defense ministers’ meeting in Tokyo, agreeing to step up cooperation on maritime security. Indonesia, which is modernizing its defense capabilities, has shown interest in MSDF frigates and older submarines. During the visit to Japan, Indonesia’s Defense Minister Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin toured a frigate, a destroyer and a submarine at the MSDF's Yokosuka Naval Base alongside Japan’s Defense Minister Shinjiro Koizumi. Koizumi said : “Transferring defense equipment is a key policy tool for shaping a more stable security environment, and Japan intends to strengthen its high-level outreach to partner countries. Today was exactly the kind of opportunity we need.”

Japan’s Defense Industry Gains New Momentum

Japan’s defense industry rests on an exceptionally broad base. Roughly 1,100 companies feed into the production of the F-2 fighter, about 1,300 support the Type 10 tank, and an astonishing 8,300 are involved in building a single MSDF frigate. Yet despite this scale, the sector remains overwhelmingly domestic, with most orders coming from the Ministry of Defense. That structure forces manufacturers to turn out small batches of highly varied equipment. Because years often pass between orders, people in the industry wryly refer to this pattern as “long-time-no-see production.”With limited room for growth and low profit margins, more and more companies had been pulling out of Japan’s defense sector. That began to shift in December 2022, when the administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida approved a sweeping increase in defense spending — 43 trillion yen over five years. Incumbent Prime Minister Takaichi has accelerated the plan, bringing forward by two years the goal of raising defense expenditures to 2 percent of GDP, now slated for completion within fiscal 2025. Japan’s defense industry is turning into a business where companies can genuinely make money.

On November 13, 2025, NEC Corp. announced that it will boost staffing for its defense division by 1,600 people by the end of fiscal 2025, compared with fiscal 2020 levels. The company has established strengths in sensors, networks, and information technology. Hiroyuki Nagano, NEC’s corporate executive vice president overseeing the defense business, expressed confidence in the company’s trajectory, noting that “the Ministry of Defense is putting its greatest emphasis on space, cyber, and electronic warfare — areas where we are particularly strong.”

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), five Japanese companies ranked among the world’s top 100 defense contractors by sales in 2024: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (32nd), Kawasaki Heavy Industries Ltd. (55th), Fujitsu Ltd. (64th), Mitsubishi Electric (76th), and NEC (83rd). Yet even Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Japan’s top performer, generated only 5.03 billion dollars in defense sales —less than one-tenth of the 64.65 billion dollars posted by global leader Lockheed Martin. If the five-category restriction is lifted, Japan’s defense industry could tap into far broader markets and draw in new players, including startups. With Japan’s strong technological capabilities behind it, “Made in Japan” defense equipment has the potential to make a major leap forward.

Japan’s move to export defense equipment as a way to deepen cooperation with allied and like-minded partners represents an evolution of the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) vision put forward by former Prime Minister Abe. Through these transfers, Japan is positioning itself as a “responsible state” — one that bolsters international deterrence and helps underpin stability across the region.

By Akio Yaita

Journalist. Graduated from the Faculty of Letters at Keio University.

After completing his doctorate at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, he worked as a correspondent for the Sankei Shimbun in Beijing and as Taipei bureau chief. Author or co-author of many books.

*The stories and materials above are provided by JIJI.press or AFPBBNews. Feel free to feature these stories in your own media, as long as they are properly credited.